George Livingston M.S. in Biochemistry

Introduction

The main issue with vaccinating against parasites is their complex life cycle. Plasmodium species infections that cause malaria, for example, have portions of their life cycle that are specific to the midgut and salivary glands of an Anopheles mosquito, and other portions that are specific to different anatomical locations of a human host [1]. This complexity is the case for most parasitic infections, but there is a distinction to be made here about classifying parasitic life cycles as complex because some are deemed “simple.” If a parasite completes its life cycle in a single host, then it can be classified as a simple life cycle parasite (SLP), but if it takes multiple hosts for a parasite to complete its life cycle, then it is considered a complex life cycle parasite (CLP) [2]. Plasmodium is considered a CLP because it requires multiple hosts [2]. Other problems with developing vaccines for plasmodium infections include challenges in understanding natural immunity mechanisms, antigen complexity, choosing a life cycle stage to target, antiparasitic drug resistance, and socioeconomic logistics [3,4].

Background

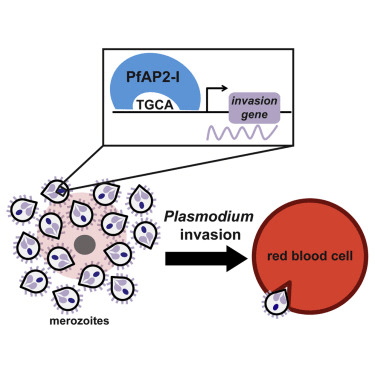

Malaria is the disease associated with 5 main infectious plasmodium species in humans: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. knowlesi [1]. Each species has slight changes in their malarian etiologies, but a significant difference in P. knowlesi is the addition of a host in the life cycle; most malaria caused by plasmodium occurs by cycling from mosquitoes to humans, but P. knowlesi has part of its life cycle in mosquitoes, humans, and monkeys (macaques) [1]. The significance of CLPs versus SLPs is in CLPs being able to escape the restrictive forces of “growth or reproduction [2].” CLPs escape this trade-off when moving between hosts. When in different hosts, growth and reproduction factors can evolve independently with sexual and asexual reproduction occurring within different organisms; in a single organism, this type of evolution is restricted [2]. Diagnostic strategies for diagnosing malaria include context (geographical location and mosquito presence) and symptoms (fever, headache, chills, sweating, diarrhea, muscle aches, nausea, vomiting, and in severe cases altered mental state, seizures, anemia, symptoms associated with altered liver function, and impaired kidney function) [1,5]. The generic life cycle of plasmodium includes sporozoites in mosquito saliva entering the skin and bloodstream of a human host. Then, plasmodium sporozoites circulate in the blood until they reach the hepatocytes in the liver where they asexually replicate after entering the hepatocytes [1]. During the hepatic/pre-erythrocytic stage, infected hepatocytes rupture and release thousands of merozoites into circulation [1]. Some strains of plasmodium (P. vivax and P. ovale) can enter a dormancy state in hepatocytes (expressed as hypnozoites) to evade host immune responses for weeks, months, or up to 4 years [1]. This dormancy can subside opportunistically during times of immunosuppression and cause malaria relapses [1]. This results in erythrocytic infection which causes most of the signs and symptoms associated with malaria [1]. During this stage, host erythrocytes are deformed and merozoites adjoin themselves to the erythrocyte membrane [1]. Reorganization of RBC’s cytoskeletons occurs after the binding between merozoites and the erythrocyte’s membranes, and this event is what allows the parasite to infect these RBCs and the second round of asexual reproduction occurs within the host’s RBCs [1]. Merozoites that asexually reproduce within erythrocytes produce trophozoites that protrude through the erythrocyte membrane as schizonts and cause the erythrocyte to rupture which releases more merozoites into circulation [1]. Different strains of plasmodium have specific affinities for differently aged erythrocytes [1]. The sexual reproduction of plasmodium occurs in the midgut of mosquitoes, so for this to occur, a mosquito must bite an infected human and have enough of the parasitic gametocytes pass from the human’s blood into the mosquito [1]. The parasitic gametocytes are produced in the human’s RBCs by trophozoite maturation into male and female gametocytes [1]. Within the midgut of the mosquito, fertilization occurs after the male and female gametocytes mature into fertile gametes that fuse to form the zygote [1]. In the mosquito’s midgut basal lamina, the zygote will develop into ookinetes, which mature into oocysts [1]. These oocysts grow and release sporozoites that move to the salivary glands of the mosquito where the next mammalian host can be infected via bite transmission [1]. The life cycle complexity of the plasmodium strains that cause malaria show how it would be difficult for the host’s immune system to recognize such a variety of cell types and associate them with the same infectious agent. Still considering life cycle complexity, choosing where to effectively intervene in the process for the purpose of vaccination has been troublesome [3,4]. There are many vaccine trials that have yielded disappointing results, but one of the most significant vaccines showed that 77-79% of plasmodium naive adults were able to have sustained immunity against infection for 9-10 weeks following five doses of 2.7 × 105 PfSPZ Vaccine or three doses of 1.8 × 106 PfSPZ Vaccine [3]. However, adults with previous plasmodium infections causing malaria only saw a 51-52% efficacy on the same regimen. Even with both numbers showing promise, there is still more work to be done before reaching the Malaria Vaccine Technology Roadmap’s goal of developing vaccines by 2030 with at least 75% protective efficacy against P. falciparum, especially with requiring sustained immunity for at least 2 years [3]. Antigen complexity can be difficult as well because plasmodium has many surface proteins that vary by strain, and the parasite has potential to mutate and render the vaccine ineffective [4]. P. falciparum is the most prevalent malaria parasite globally, so it is no surprise that it continues to develop resistance to antiparasitics such as chloroquine [1]. Considering the logistics of developing vaccines, funding is an issue for any type of development or research, and government backing is paramount for continued progression in vaccine development because they are costly and can take several years [4]. Unfortunately, it is difficult to justify funding projects that do not significantly affect the population that a country serves because the more affluent and stable countries are not heavily affected by malaria [4]. Still, 1.5-2.7 million people die per year from malaria infections, but these are almost exclusive to the impoverished and unstable countries that the disease is endemic to [5].

Vaccine Efficacy Challenges Relating to Infection and Life Cycle Specifics

The growth or reproduction trade-off specific to SLPs is not an issue for CLPs like plasmodium species. As was explained previously, CLPs have a greater ability to grow and reproduce due to sexual reproduction occurring in one host while asexual reproduction occurs in another host [2]. This means that CLPs are more difficult to fight against than SLPs. The figure below shows how having multiple hosts is beneficial for CLPs (b) compared to SLPs (a):

Furthermore, multiple hosts facilitates the spread of disease [1,2]. In the case of plasmodium species that cause malaria, mosquitoes can travel from host to host across some distance and bite/infect multiple humans. The figure below illustrates this host migration:

With mosquitoes being able to fly, isolating outbreaks of malaria in endemic countries is very difficult [2,4]. This host migration can only be lessened by treating for mosquitoes, but most methods for deterring or killing mosquitoes cause collateral damage on the human population and other insect populations as well.

When considering where a vaccine should intervene in the life cycle of plasmodium species, there has been a lot of trial and error [3]. Asexual blood stage vaccines, whole parasite blood vaccines, sub-unit blood stage vaccines, placental malaria vaccines, transmission blocking vaccines, pre-erythrocytic blood stage vaccines, non-circumsporozoite protein sub-unit pre-erythrocytic stage vaccines, and a myriad of other trials have lead to the first recommended and implemented malaria vaccine for young children at high risk for contracting malaria [3]. The currently recommended vaccine is known as the RTS,S/AS01, and in 2021, it was specifically recommended to combat P. falciparum in high risk children [3]. The vaccine works by intervening at the sporozoite stage by a vaccinated individual’s adaptive immune system being able to recognize the circumsporozoite proteins (CSPs) on the surface of the plasmodium when an infected mosquito bites a human [3]. Ideally, the presence of plasmodium would be recognized by memory B cells that can differentiate into plasma cells that produce antibodies. Unfortunately, plasmodium will invade hepatocytes approximately 30 minutes after the infectious mosquito bite, but memory B cells take a bit longer to differentiate into plasma cells and generate a robust immune system response [3]. However, this initial recognition helps “sound the alarm” and prevent a severe infection, but that is a major issue with the efficacy of the RTS,S/AS01 vaccine because it lessens the severity of the case and may prevent some cases, but many of the children vaccinated with the RTS,S/AS01 will still contract malaria to some extent [3]. The exact efficacy of the RTS,S/AS01 vaccine varies depending on several factors such as degree of exposure, malaria infected versus malaria naive humans, age, and completing vaccination series, but approximately 50-55% efficacy was sustained for several years in groups that received and finished the vaccination series when they were children [3].

Vaccine Efficacy Challenges Relating to Logistics and Access

Access is a big problem for any kind of vaccination since some areas can be difficult to reach and funding can be tough to attain [6]. For example, African countries often lack the resources to purchase and distribute vaccines effectively [6]. Additionally, limited funding restricts research and development of new and improved vaccines [6]. The complex logistics of delivering vaccines to remote areas with limited infrastructure fragment supply chains, so even if medicine and vaccines are scheduled and sent for delivery, it may take longer than expected to reach their destination (depending on where it is being delivered) [6]. Plus, some malaria vaccines require storage at specific low temperatures, and one such vaccine is the RTS,S/AS01 [6]. Maintaining this refrigeration throughout transportation and storage can be difficult in Africa, for power outages and inadequate infrastructure to support refrigeration is common [6]. There is also some vaccine hesitancy due to misinformation, cultural beliefs, and concerns about side effects [6]. However, in 2022, 462,080 children under the age of 5 died due to plasmodium infections leading to severe malaria, so more research, funding, and action is required for preventing some of these tragic deaths [6].

Conclusion

The complex life cycle of Plasmodium parasites presents a significant challenge in developing effective malaria vaccines. Their ability to undergo sexual reproduction in one host and asexual reproduction in another allows them to evade the limitations faced by single-host parasites. Furthermore, the multiple hosts involved in the malaria life cycle, particularly the mosquito vector, complicate efforts to control transmission. Despite these hurdles, research has yielded a promising vaccine, RTS,S/AS01, which targets the sporozoite stage. However, even with some efficacy, this vaccine does not fully prevent infection and achieving widespread vaccination coverage is hampered by logistical and access issues in many malaria-endemic regions. Continued research and development efforts are crucial to overcome these challenges and achieve the goal of a highly effective and accessible malaria vaccine.

References

[1] Fikadu M, Ashenafi E. Malaria: An Overview. Infect Drug Resist. 2023 May 29;16:3339-3347. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S405668. PMID: 37274361; PMCID: PMC10237628.

[2] Auld SK, Tinsley MC. The evolutionary ecology of complex lifecycle parasites: linking phenomena with mechanisms. Heredity (Edinb). 2015 Feb;114(2):125-32. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2014.84. Epub 2014 Sep 17. PMID: 25227255; PMCID: PMC4815630.

[3] Stanisic DI, Good MF. Malaria Vaccines: Progress to Date. BioDrugs. 2023 Nov;37(6):737-756. doi: 10.1007/s40259-023-00623-4. Epub 2023 Sep 20. PMID: 37728713; PMCID: PMC10581939.

[4] Knox DP, Redmond DL. Parasite vaccines – recent progress and problems associated with their development. Parasitology. 2006;133 Suppl:S1-8. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006001776. PMID: 17274842.

[5] Buck E, Finnigan NA. Malaria. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551711/.

[6] Olalekan John Okesanya, Faith Atewologun, Don Eliseo Lucero-Prisno, Olaniyi Abideen Adigun, Tolutope Adebimpe Oso, Emery Manirambona, Noah Olaleke Olabode, Gilbert Eshun, Abdulmajeed Opeyemi Agboola, Inibehe Ime Okon. Bridging the gap to malaria vaccination in Africa: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, Volume 2, 2024. 100059, ISSN 2949-916X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glmedi.2024.100059.

[7] Joana Mendonca Santos, Gabrielle Josling, Philipp Ross, Preeti Joshi, Lindsey Orchard, Tracey Campbell, Ariel Schieler, Ileana M. Cristea, Manuel Llinás. Red Blood Cell Invasion by the Malaria Parasite Is Coordinated by the PfAP2-I Transcription Factor. Cell Host & Microbe. Volume 21, Issue 6. 2017. Pages 731-741.e10. ISSN 1931-3128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2017.05.006.

Leave a comment